Guillermo del Toro’s Frankenstein (2025): Reviving Mary Shelley’s Gothic Masterpiece

Table of Content

Pain Filmed on Screen

When I finished watching Guillermo del Toro’s Frankenstein (2025), I just sat there, quiet, stunned, and almost hollowed out. This film isn’t simply horror, romance, or gothic tragedy. It is pain; captured on screen with a tenderness that hurts to watch. Del Toro doesn’t just adapt Frankenstein; he feels it. He approaches Shelley’s story not as a tale about monsters but as a meditation on pride, hubris, grief, and the desperate ache to be acknowledged by the one who made you.

Ever since the movie came out, conversations online have been circling its themes: childhood trauma, father-son wounds, the fragility of connection, the brevity of love, and the way a single moment of abandonment can shape an entire life. All of these discussions seem to arrive at the same overwhelming truth: existence is painful, it’s melancholic, and life, as beautiful as it might be for some, is often unbearably hard and tragic, and yet we all keep trying to live it anyway.

If you like emotionally heavy stories, you might enjoy what I’ve been digging into about the renewed buzz around Fyodor Dostoevsky.

Shelley’s Vision and Del Toro’s Reimagination

Mary Shelley wrote Frankenstein at just eighteen, as part of a story competition that accidentally birthed the first work of science fiction. Beneath the lightning and laboratories, her story was always emotional, portraying human suffering and rejection. A very important point in Shelley’s Frankenstein is that the Creature is beautiful. Victor’s creature in the book had proportioned limbs, beautiful features, lustrous black hair, and pearly white teeth. But it all seemed horrible to Victor when contrasted with his watery eyes.

If you’d like a full review of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, I’ve written one on my Medium profile. Click to read full book review.

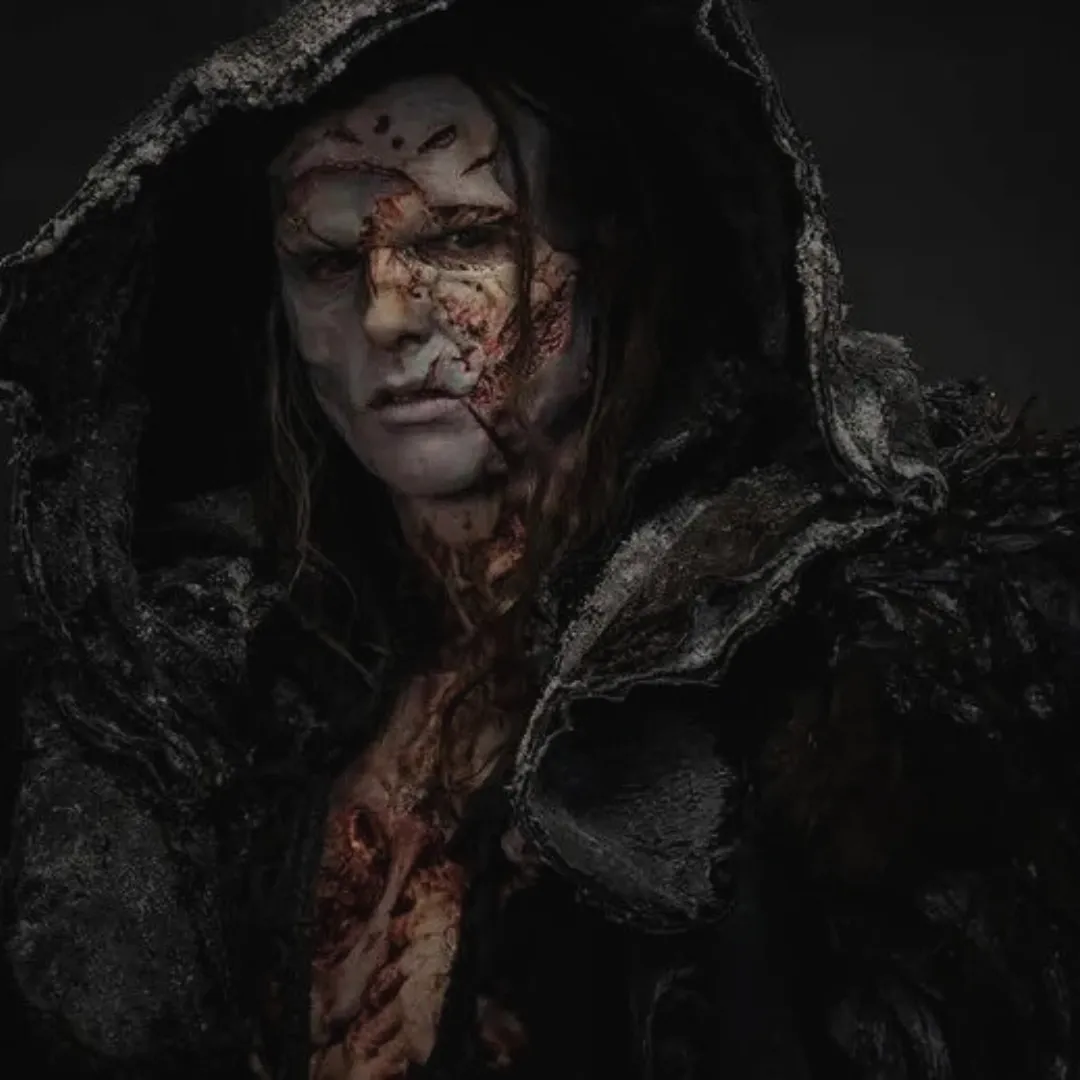

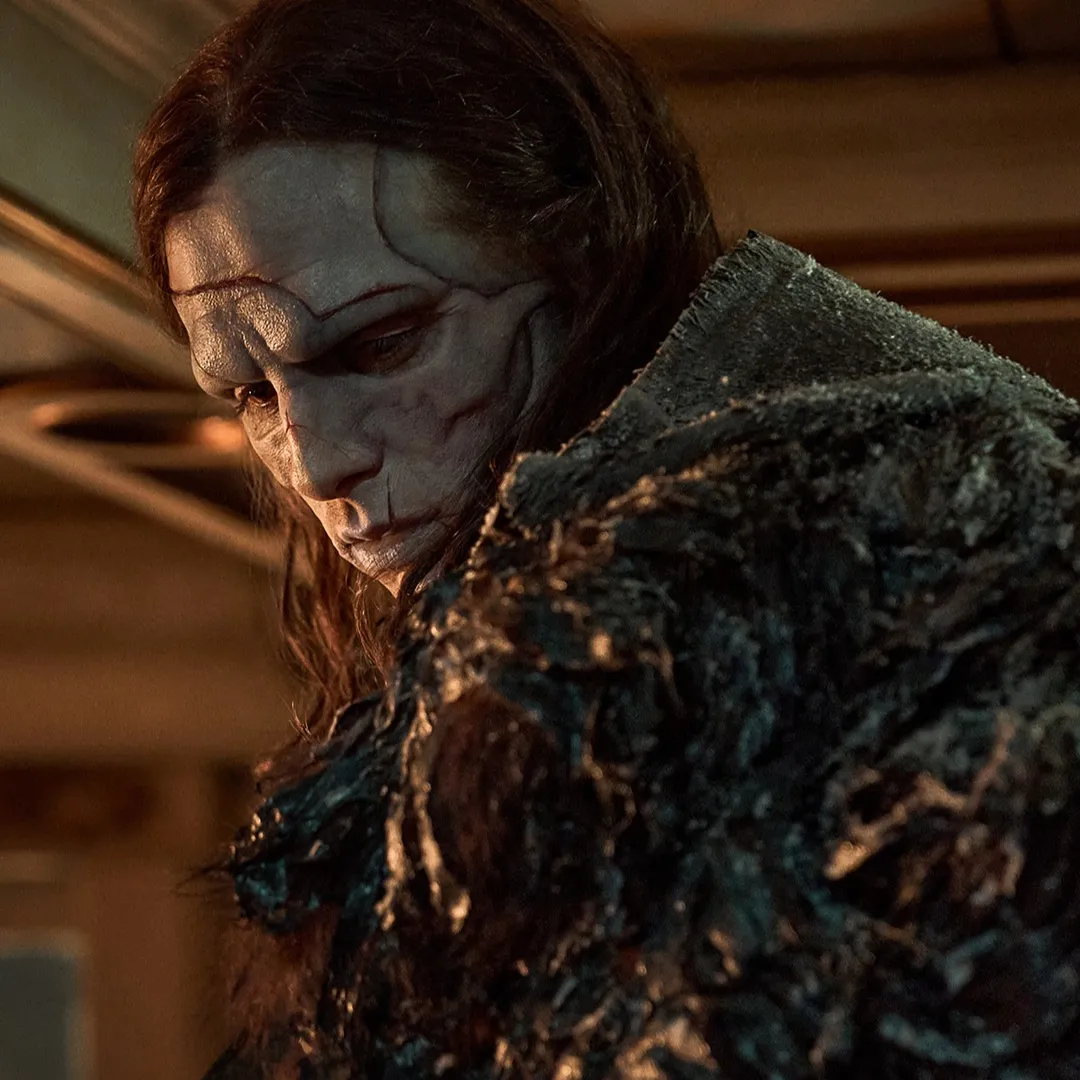

The details I have been referring to regarding the Creature matter a lot. These details have been distorted and changed over time. Shelley never called the Creature ugly; she called him beautiful. He might not be beautiful to Victor, but he was never ugly as we have always seen him. Most adaptations created a green big monster with its eyes barely visible. Del Toro didn’t. His Creature, played by Jacob Elordi, is hauntingly symmetrical, graceful, imperfect in some ways, but mesmerizing to look at, especially because of those deep watery eyes.

Guillermo del Toro doesn’t preserve Shelley’s story scene by scene, but he revives her spirit in the film adaptation. He understands that pain changes with each generation, and in reshaping and reimagining the myth, he makes it ours again.

Science, Sorrow, and the Birth of Pain in Frankenstein

Del Toro’s scene of creation is unlike anything we’ve seen before. Gone is the mysterious It’s alive! moment. Instead, we witness the raw anatomy of birth with lymph nodes, veins, muscle, and every tiny detail. It’s grotesque and sacred at once, as if we’re watching both a miracle and a sin unfold.

The process is filmed with reverence: it’s slow, deliberate, and unsettlingly beautiful. We see how he creates the Creature piece by piece. Del Toro forces us to confront what creation actually means. To create is to destroy something else, to reorder nature, to assume the power of gods without understanding its cost. That’s what makes this sequence so powerful.

Victor Frankenstein: The Creator Who Cannot Love

Oscar Isaac as Victor Frankenstein is terrifying not because he’s visibly mad, but because he’s calm, methodical, and precise. He doesn’t simply want to create life; he wants to control and master it. He craves perfection, and when his creation fails to meet that ideal, he recoils. The true horror lies not in his ambition, but in his indifference.

Victor’s flaw isn’t just pride, it’s fear, insecurity, and that familiar fatherly panic of wondering why his son isn’t perfect. He can’t love what he has created because the world he comes from barely allows men to love their creations at all. Patriarchy trains fathers to control, not to nurture. So Victor recoils and becomes wildly aggressive when someone like Elizabeth later shows what unconditional love actually looks like.

When Victor starts hunting the Creature, it only exposes his own insecurity as a creator. He wants absolute control over another life, as if that would erase his mistakes. His brilliance is tangled up with obsession and pride, making him just as tragic and just as unhinged as the thing he brought to life.

Del Toro softens Victor’s villainy at the end by portraying him as a man who changes, who ultimately accepts the Creature as his child. He is not evil by nature, but suffocates under the weight of his own creation. That tension, between brilliance, fear, obsession, and the inability to love, makes him a profoundly tragic father figure.

The Creature: The Weight of Existence

From the moment he breathes, the Creature is abandoned. Alone, unprepared, and terrified, he wanders like a newborn trapped in an adult body. Elordi captures this perfectly: the trembling hands, the watery eyes, the way he learns to walk and speak. Every movement aches with confusion and wonder.

There’s a beautiful moment when he encounters a wild stag, a fleeting glimpse of connection. For a second, he belongs. But the world quickly reminds him that it follows a vicious order. He realizes

An idea, a feeling became clear to me. The hunter did not hate the wolf. The wolf did not hate the sheep. But violence felt inevitable between them. Perhaps, I thought, this was the way of the world. It would hunt you and kill you just for being who you are. — Frankenstein (2025)

This is the film’s truth: existence is painful, survival is cruel, and yet we keep trying. Even when he wants to die, he simply cannot. He has to live and he has to accept whatever life offers him because there is no other choice.

I do sense that del Toro’s Creature leans more toward the saintly than the volatile. He kills only in self-defense, never from rage which is a notable shift from Mary Shelley’s original intent. It made me wonder what this change is meant to highlight. After all, with so much pain, wouldn’t some of it spill over? Perhaps del Toro wanted to emphasize that the true cruelty lies with humans, not the Creature.

But the more I think about it, the more this gentler portrayal feels like watching a child grow up in real time. And a child, no matter how strange or powerful, doesn’t turn vengeful on their own. They reach out for acknowledgement, affection, and a place in the world. That’s exactly what we see in this Creature. So maybe (without betraying Shelley’s spirit), del Toro offers a version of the Creature that’s even more human, more heartbreaking, and in its own way, more compelling

Elizabeth: The Courage to See Beyond Beauty

Mia Goth as Elizabeth is one of del Toro’s most beautiful additions. She is Victor’s moral opposite, empathetic, curious, and unafraid of ugliness. Her fascination with insects mirrors her ability to see beauty beyond the surface.

When she looks at the Creature, she doesn’t see horror; she sees humanity. Their connection isn’t only love, it’s recognition and acknowledgement. They find a rare connection that they have always yearned for in their lives. In one of the film’s best lines, she shouts, Only monsters play God, Baron! and you feel the courage it takes to confront both genius and evil. Del Toro gives Elizabeth a depth Shelley never had room to explore. She is the perfect tragic heroine from the past who feels relatable to the modern audience.

Elizabeth’s fate is similar in both novel and film but del Toro makes it more compelling and powerful than in the book. She is not killed by the Creature, she is rather rescued and loved by him. She is the victim of Victor’s wrath and hubris who shoots her while trying to kill the Creature. This change makes it easier to sympathize with the Creature and elevates Elizabeth’s status as a tragic heroine and not a side character.

The Beauty of Suffering

Every frame of Frankenstein (2025) is pure gothic poetry. The ruins of a forgotten castle, rain and thunder as characters, symbolic costumes, and a silence that speaks louder than screams. The film is extremely artistic and as good as you could possibly hope. The artistic references are so subtle, beautiful, and mind-blowing at the same time. There’s a scene where Elizabeth and the Creature reach out and touch hands which reminded me of Michelangelo’s Creation of Adam.

The pain in Jacob Elordi’s eyes reminded me of The Fallen Angel by Alexandre Cabanel. The only difference being, unlike Lucifer, the Creature has never been Victor’s favorite.. Del Toro doesn’t romanticize Creature’s suffering, he acknowledges it and paints it like a work of art. The suffering is beautified, but that’s what makes it more heartbreaking. It is beautiful and yet so melancholic, so sad, that you can barely forget it.

The film made me believe that the Creature is still out there somewhere, wandering alone through the northern snowfields, hidden from a world that never deserved him. There’s something haunting about that thought: this gentle, wounded soul exiled not because he was monstrous, but because we were. It feels as though humanity failed him completely, pushed him into isolation, and in doing so, lost something achingly beautiful.

Watching the Creature made me think of Edward Mordake, the man with two faces, whose story, though fictional, fascinates in similar ways. I’ve explored the full case here.

Final Thoughts

Del Toro’s Frankenstein isn’t really about science or vengeance; it’s about the pain of being. The pain of birth, of loneliness, of abandonment, and the fleeting nature of love. It’s about what happens when a creator cannot love, and a creation cannot stop longing to be loved

Del Toro doesn’t modernize Shelley; he humanizes her. He gives her Creature the beauty, fragility, and depth he has always deserved. I don’t remember ever feeling the Creature’s sorrow this sharply. I’ve always seen him as tragic and innocent, but Del Toro makes him unforgettable with those teary eyes, the sharp features, the graceful symmetry, and the unbearable ache he carries. This is the kind of revival a classic deserves: bold in its changes, yet somehow truer than expected.

And for that reason, this film earns a place in my Reader’s Choice recommendations. It’s not just another adaptation, it’s a must-watch for the season, a haunting, heartfelt reimagining that honors Shelley while breathing entirely new life into her masterpiece. If you’re looking for something that lingers long after the credits roll, this is it.

References:

Shelley, Mary. Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus. Lackington, Hughes, Harding, Mavor & Jones, 1818.

Frankenstein. Directed by Guillermo del Toro, Netflix, 2025.

Promotional images courtesy of Netflix.